When Lawrence died, it was a mild inconvenience. That may sound cold but I could never lie about this- I did not love him. Our fathers insisted upon us marrying as a fertile tie for their companies and that was that. My daddy owned a furniture store and Lawrence’s father ran a logging mill. They congratulated themselves on their genius. I was twenty-three with no other suitors and Lawrence was indifferent.

As our fathers brought us together in the office of their new logging company he shrugged at the suggestion of marriage. I looked down at my shoes and then caught his eye, resolving on bravery, and what I saw there I will never forget: he was a man incapable of affection. He was caught on this earth, but he belonged elsewhere- somewhere sombre and self-serving, somewhere where Lawrence could legally and morally care solely about Lawrence.

But when Jack disappeared I folded in on myself and eclipsed my birthright over the course of six months. The preacher was the one who said the words. The women of Concrete could only whisper them as I passed. Children died; it happened all the time. And while mothers were never truly the same, they simply had more. They buried their memories with the tiny coffins and got on with the business of living. Or so my twenty-nine-year-old heart told me.

I was a widow with a missing child who was unwilling to accept the inevitable. This made me difficult, strange, and a pariah. No one wanted to reason with the unreasonable. They all had problems of their own, but I refused to leave. Our cabin home was the only place that Jack had known and I would not abandon it. This meant people felt obliged- to bring me food, to quote scripture as they rubbed my hand and to repeatedly suggest I go home to my family.

My gut and heart fought battles with my mind. Jack was alive in the former, feared dead in the latter. Most mornings were met with shaking hands and lips dry from forgetting to drink water, never mind eat anything. Sleep came in two-hour bursts out of sheer exhaustion and the hope that he might meet me in dreams and guide me to where he was. We had a connection to be sure, but panic had caused a thick and awful fog to take hold and I could not seem to get to him.

And so each morning I would wake to the picture of Lawrence and me on our wedding day (barely-masked frowns and all) say to myself that I didn’t need to keep it anymore, and I would grab my grandmother’s cross. Knees wearily dropping to the floor, I would pray. And then I would force a bite of apple and cold tea into me before donning my cape and heading out into the woods.

I used to love these woods. I used to feel sheltered and protected by them. They kept Lawrence at work and shrouded me in privacy. I could cook and wash and fold in peace. And they were a playground for my son. But now…

Every sound mocked me. Every whistling wind, every cicada’s trill, every howl of the wolf- each held empty promises of a clue within them. They each held the potential of Jack’s cries and they always came up wanting. If I focused on them, I grew mad with obsession. I had to learn to let them fall back and lean on my mother’s instinct instead. Blaming myself for his loss in the first place meant this was difficult.

I finally resolved to get up and make it to the cabin. My skirt was covered in mud and leaves but what did it matter? I’d been wearing these clothes for days. The cabin would be cold, so cold…

Building a fire was good, I reminded myself. The smoke would signal to Jack that Mama was home and waiting for him. It was the right thing to do, I decided. I felt my sanity slipping at odd moments. Doing something as simple as building a fire held the promise of keeping it together.

I made it to the woodpile and gratefully piled logs and kindling into the folds of my cape. Lawrence had chopped enough for the coming autumn and winter. He was good for something it seemed- wood and sons.

My son.

And as I walked back to the cabin, I prayed for Jack to hear me and come back home.

<3

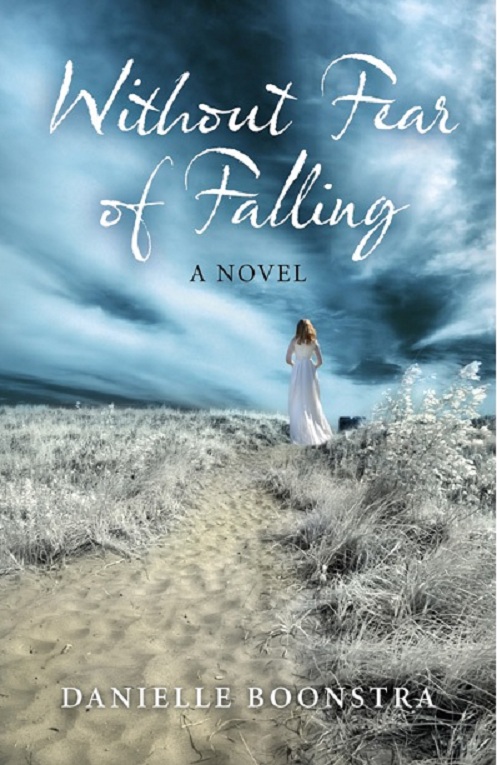

Photo by Taylor Ann Wright on Unsplash